Filming is disruptive at best. When The Guibord Center’s Board of Directors and Advisory Council agreed to allow us to film them in their sacred sites, they did so because every one of them was eager to support this initiative. They wanted to do something, whatever they could, to end cruelty to animals. I doubt that any one of them measured the cost, to themselves or to their communities. It was just the right thing to do.

Late in our second day I began to realize what a hassle and disruption this filming was. It takes a great deal of time and care to set up a powerful shot – and just as much time to tear it down step by step and put everything back exactly as it was before we began. And then there is the issue of each piece of equipment that needs to be broken down itself, carried outside and carefully packed to be transported to the next location.

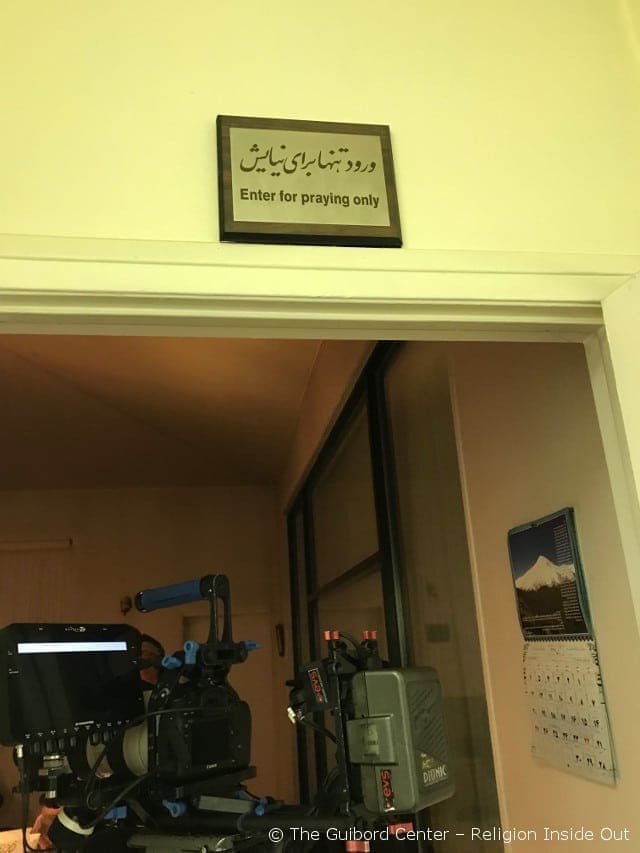

It all takes time, time when a congregation, a community, is displaced from the location that is most intimate and precious to them. In an act of immense graciousness, for a set period of time, they give over the use of their own most tender home to strangers, often strangers who do not speak the language of their faith or practice its tenets.

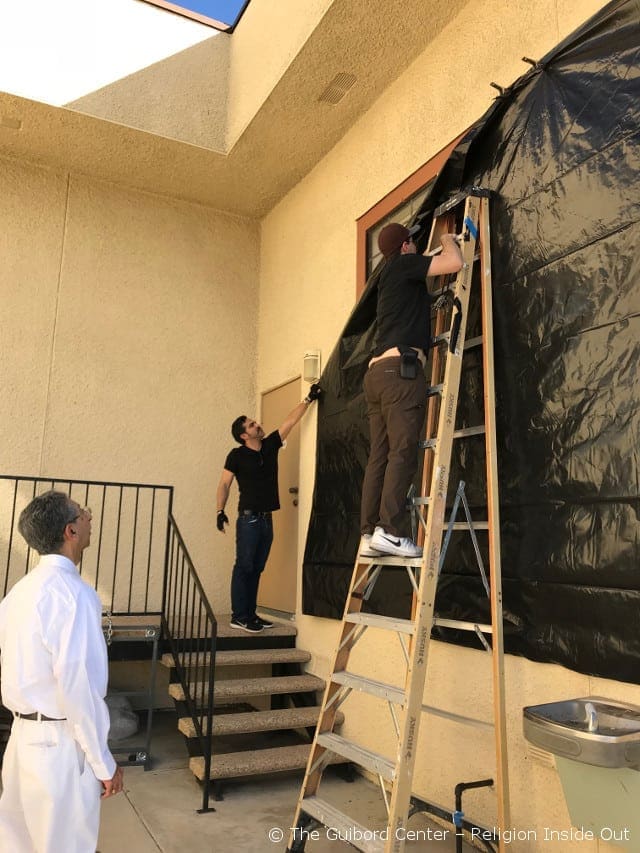

The California Zoroastrian Center, like most of the places we filmed, is more than a place of worship, it is a place for the community to come together to celebrate those occasions that are special and reflect their faith. The Saturday of our filming was one such occasion. We had arrived early in the morning to black out the windows of the prayer room. We had worked carefully and as quickly as we could around an unexpected pile of concrete blocks near the stairs where it appeared some project was underway. The going was slow.

People started arriving around midday to prepare for a celebration to be held that night. Young people were rehearsing their parts for a performance. Men and women brought in food. They could not get into their prayer room or conduct their activities with abandon because we were still at work late in the afternoon.

The unforeseen Chinese New Year’s Celebration in the parking lot next door had set us back. We’d been racing to catch up ever since. As the shadows grew, more and more people began arriving. The parking lot by the prayer room was filling quickly as we pulled equipment out of the room and laid it on the grass just outside in an effort to return it to the pristine state it was in when we began. Two elderly women tried to climb the stairs to get to their sacred flame and were told they had to wait. They walked over to a bench and sat down quietly.

As others gathered, they began to inquire of one another about what had happened to their “project”. Why had we taken down the concrete wall and left a mess? Why had we not cleaned it up along with the heavy plastic sheeting we were clearing away? There was confusion. Apparently someone had been building a ramp for handicapped folks to use to get up to the prayer room, but unbeknownst to them the project had been cancelled. The pile of blocks we worked around still lay there on the ground right where we found them that morning.

So here we were, thought to be perpetrators of a violation to their space, clearly running late, unintentionally violating our agreement to be gone by 5:00 pm, holding up their prayer and their celebration. And what did they do?

They invited us to stay for dinner, to come and join in their party. They brought us water. Offered tea. Treats. Carefully explained the joyful occasion as some kind of blending of Valentine’s Day and Mother’s Day and something else I didn’t quite catch. I confess, I would have been annoyed.

Zarathushtra taught that we are each responsible for our own behavior: to choose good and stay away from that which is evil. The basic formula of the Zoroastrian faith is written high on the entrance of the Center and on the mirror we had seen all day long. “Good Thoughts.” “Good Words.” “Good Deeds.”

Sometimes the things that happen in the in-between moments, the moments of tension and misunderstanding, are the things that offer the greatest lessons. The measure of faith is always how we treat one another.