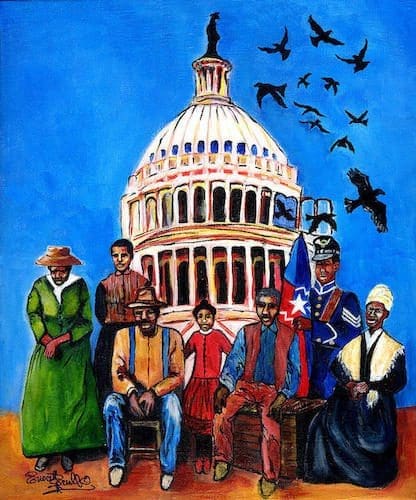

Image: Freedom: Celebrating Juneteenth by Everett Spruill

Juneteenth and the Soul of America, Part 2

This two-part blog post is adapted with permission from Juneteenth and the Soul of America, a presentation given for Interfaith Communities United for Justice and Peace (ICUJP) in June 2020.

Juneteenth as Signifying Moment

None of the first Juneteenth celebrants were under the illusion that the Emancipation Proclamation and the subsequent amendment were an actual declaration of freedom and full citizenship. To be clear, it was progress, and better than the whip and the chain, but not full enfranchisement. It was viewed more as a down payment on a promise yet to be fulfilled. Juneteenth was and is an occasion for coming together as a community to celebrate what God has wrought thus far. A time to acknowledge the sacrifices, lost lives, and suffering of those who lived in hope of a better tomorrow, in hope of freedom’s sweet sound.

The late Bishop and theologian Dr. Ithiel Clemmons, of the Church of God in Christ, the largest Black Pentecostal denomination in the US, stated: “Celebrations provide opportunities to reexamine the power, influences, strengths and weaknesses of the original vision in light of history. They give a new generation the opportunity to reflect upon who and why they are and to make a decision about their commitment to carry forward with that vision.” (Clemmons, 1993) Juneteenth offers this type of occasion.

And so on one level, merriment, barbecues, picnics, music, parades and other forms of celebration, red soda water, homemade muscadine wine and gin mark the event. Yet on another level, there is a profound spiritual encounter with the ancestors and the community’s vision for itself, the country and the world. Juneteenth finds at its core an existential moment and hope that transcend current circumstances, no matter what they seem.

Conditions and Challenges

What was the intention and basis for this declaration of Emancipation? The General Order read by Granger casts the definition of freedom in economic terms. The proclamation gave a salute to personal and property rights, but discussed the abolition of slavery and the reorganization of work relations between the formerly enslaved and the erstwhile enslaver. It also admonished the freed men and women about idleness and that essentially “there is no free lunch.”

Clearly, Lincoln’s intention in declaring the emancipation was a tactical maneuver. He states in a letter dated August 22, 1862, “If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that.”

Reparations for previous injustices should be the option of a human being who was wronged and injured. This was brought up but never came to fruition. On January 16, 1865, Union General William T. Sherman issued Special Field Order No. 15, which redistributed roughly 400,000 acres of land confiscated from Southern planters to newly freed black families in 40-acre segments. This order was never carried out. Reconstruction, which lasted from 1865 to 1877, made efforts to redress the inequities of slavery and its political, social, and economic legacy. These efforts, however, were quickly derailed and abandoned.

During these years, Blacks enjoyed civil liberties in the South and were able to vote, with some holding elective office at various levels. This period was short lived. Soon came the rise of the KKK, voter intimidation, public lynchings as spectacle, church burnings and attacks on Black communities. Blacks were driven from Southern states out of fear and violence to other parts of the US, such as the industrialized Northeast, Midwest and West.

“Freedom” Then and Now

My maternal grandfather and grandmother, pregnant with their first son, were also part of these great migrations. They fled Selma, Alabama in 1917, stopped in Louisville, Kentucky to give birth, then settled in Cleveland, Ohio. I would venture that every African American family has a story of forced migration.

What made this terrible circumstance palatable for many, in addition to the amelioration of racialized violence primarily directed at Black men, was the hope of finding a better life on the other end of the trail. They migrated from fear and violence, which were known, to a future that was unknown, an act of tremendous faith and courage. This act is currently reflected in the migration stories of immigrants we see on our borders and in detention centers.

For the next years, the country witnessed a dramatic increase in racialized violence, including riots and other attacks. One of the most infamous occurred in Tulsa, Oklahoma on May 31 and June 1, 1921, on the eve of Juneteenth, scorching the Greenwood District. An estimated 150 to 300 people were killed, businesses and homes burned, and the hopes of a Black community that was making economic progress were dashed in the ash heap that remained. (Tulsa Race Riot of 1921 | Tulsa Library, n.d.)

Some scholars argue that the US engaged then and now in genocidal practice against Blacks.

The disparity in Black life and death in comparison to the norm speaks volumes about structural and institutional intent. Black people form 33% of the prison population, yet only are 12% of the overall population. (Gramlich, 2020) We see similar divergences in mortality, employment, poverty and literacy rates when compared to the national average. The problem Lincoln and others at the time faced was: What to do with the four million Black people who were no longer needed to pick cotton and produce?

The fact that President 45 selected Tulsa, Oklahoma as a major campaign rally site on Juneteenth is not lost on his base nor the country at large. After critical reaction to this blatant insult to African Americans and the nation as a whole, President 45 acquiesced and moved the rally to June 20th. The selection of Tulsa on this date and this time demarks the territory and racializes his election in terms that could not be clearer. (Trump’s Juneteenth Rally in Tulsa to Inflame Racial Tension | Cornell Chronicle, 2020)

Black Life in America

One consistent theme that recurs in U.S. history from 1619 to the present is the devaluation of Black life. Blacks had lived in the colonies prior to 1619 and historians and archeologists confirm a pre-Columbian African presence in the Americas. Nonetheless, there has been a consistent and concerted effort to circumscribe, delimit, deny and devalue Black life.

In 1619, a group of Africans was exchanged on the high seas for provisions. Following their settlement in Jamestown, Virginia, slavery emerged as an economic choice for agricultural production. As the need for agricultural products increased, so did the economy’s dependence on slave labor. The commodification of Black life was clearly a price the country was willing to pay, with its soul in the balance. Black life was bought, sold, auctioned, assayed, insured, cultivated like chattel, and disposed of when it proved to be of no use, problematic, uppity or challenging.

As early as 1787, the Constitutional Convention determined that the Black vote, and by extension life, would be counted as three-fifths that of Whites. Though this Three-fifths Compromise was for legislative and tax purposes, it codifies and gives voice to the prevailing view of Black life and its worth.

And so Whites justified the mistreatment of Blacks by seeing them as subhuman, an aberration of nature. While the Three-fifths Compromise quantified the value of Black life, the Dred Scott decision in 1857 qualified the value of Black life and rights. In this landmark case, the Supreme Court determined that Blacks had no rights that the white man was bound to respect. (National Park Service)

No Real Rights

What did these policies mean in practical terms? Mr. Charles Washington, who had been a slave for nearly half a century when freedom came, testified to a special examiner with the Bureau of Pensions in 1905, age 89:

“I was born in the state of Florida, and lived there until I was quite a lad of a boy and then I was sold to a man by the name of Thompson, who sold me to a man by the name of Randolph, and was then put into a traders yard at New Orleans, La., and there a man by the name of Dr. Vincent who lived on Joe’s Bayou . . . and he owned me for a long time until I was a grown man and had a wife and three children, and then Dr. Vincent . . . sold me to Mr. James Berry, who lived on the Mississippi River. …

“After I left home to go into the army, Mr. Berry carried all of his slaves who had remained at home, to the state of Texas, and have never heard of any of them. I was a married man, and had three children and he carried them to Texas, and I have never heard of them since.” (Shaffer and Regosin, 2005)

According to historians Donald Shaffer and Elizabeth Regosin, “The removal of slaves to Confederate states more remote from the war, like Texas, was not unusual. Planters in the Mississippi Valley forcibly moved as many as 150,000 slaves into Georgia and Alabama as well as Texas to prevent their liberation by Union forces.” (Shaffer and Regosin, 2005)

Mrs. Laura Smalley, a woman who lived to receive her freedom, described daily life under slavery in a 1941 interview with the Works Progress Administration. Read her story here

Using Black Lives

Black workers were used by planters in the South and meat-packing houses and industry in the Midwest and North. Black women were used to nurse White babies, cook and nourish White homes, plant and feed and comfort White fears. Black lives were used by Lincoln as a chess piece in a war game. Black lives were then used as cannon fodder in the Civil War, Westward expansion of the 1800s, Vietnam War, in Desert Storm and Desert Shield. Black lives were used to build the White House and the vast financial empires on Wall Street and Main Street that still dominate the American economy and culture. Black lives were used as experimental subjects; to serve; to entertain in sports, music, and theatre; and to create swaths of American culture.

Whites used Black lives as objects to vent frustration and ease their conscience for the sin of racism. And so the lynchings become a way of purging White conscience of its guilt, of silencing and obliterating the very object of its scorn. The blood spilled on the cotton fields and in the streets of America today cries out to God for justice. Just as Abel’s blood cried out in Genesis, so too is Black blood crying out in this Revelation of God’s justice. The jazz trumpet in its sinewy discourse, with no words, speaks volumes about the trouble we have seen. The trumpet becomes a way of quieting fears, and appropriates the transcendent tonality of Gabriel’s horn in seeking God’s judgment for this pernicious evil.

Juneteenth and the Ethical Imperative

Juneteenth is thus seen as an ethical construct, one that addresses where we are as a nation and where we ought to be. It is grounded in a particular historical circumstance, yet reaches into the present with authoritative clarity. While the first Juneteenth celebrants were not particularly literate, they understood the text and subtext of the Emancipation Proclamation and the General Orders issued by the commanding generals. The celebrants of Juneteenth read and discerned the times, the competing trends and historicity of the moment. They also understood God’s movement in the moment and that they had a date with destiny, as Dr. Martin Luther King would later say.

Juneteenth celebration on one level commemorates the act of emancipation. It says we have shaken off the shackles of slavery and are free from being owned by another human being. This is a momentous occasion, a time for mirth and merriment.

Yet, on the other level, Juneteenth is also a call to see that the promises of Emancipation are broadened to every aspect of one’s life as a child of God. It recognizes our birthright of freedom and blessing from God. On this level, Juneteenth challenges us to resume the work of freedom and not rest until we, and by extension everyone, are free.

Juneteenth is a witness to all who suffer the weight of being marginalized in this society. The palpable sense of being disregarded, dehumanized, hunted and killed is known to others in this society. Juneteenth is a repudiation and rejection of the category of “other.” By categorizing a group of people as “other,” Whites use themselves as the standard and benchmark by which to measure all others. “Other” allows the commodification of the neighbor and relieves the protagonist from ethical responsibility to treat others fairly or justly. By dehumanizing the other person, or arguing that they have some moral, intellectual or spiritual deficiency, it makes room for maltreatment of that person or group.

Immigrants from Latin America, the Caribbean, Africa and Asia fit into this category of other. Women are frequently labeled as other and not worth equal pay for equal work. LGBTQI+ people are considered other and worthy of derision and shame.

Resistance, Hope, and Redemption

Juneteenth is also a form of protest and resistance. The Blacks who celebrated Juneteenth in 1866 and later clearly understood the Emancipation was intended as a limited provision. In some ways this could be considered a cruel jest, as no provision was made to make them whole. The Emancipation Proclamation made no provision for reparative or restorative justice. It made no space in the square of public discourse for a moment of truth and reconciliation. Blacks understood that celebrating Juneteenth was a form of protest of the proclamation’s shortcomings and the continuing oppression they experienced.

Juneteenth is also an affirmation of hope, that truth crushed to the ground will rise up. That the God of tomorrow will make it right. It is a declaration that no matter what the dominant society conjures up to continue its oppression – be it the prison industrial complex; police shootings that declare open season on Black life, or gross disproportionality in health, education, mortality and wealth – there will be a redemptive day when “justice will roll on like many waters, and righteousness like an ever-flowing river.”

The beauty of Juneteenth is that at its core, it also seeks the redemption and reconstruction of White humanity. It believes that everyone can and should be treated as equals. Juneteenth believes in the restoration of justice and righteousness. It believes that the cancer of racism that eats away the humanity of those who partake in it can be cured, that Whites can be made whole.

Of particular importance are the voices of the faith community. Islam, Judaism, Christianity and Buddhism have, when operating at their best, affirmed the inestimable worth of human life. That human life is sacred and to be respected, cherished and affirmed. These faith traditions then and now have continued to challenge the prevailing ethos of dehumanization in America. They raise a challenge to police brutality, environmental degradation of God’s creation, the meanness, violence and callous disregard for the suffering of others.

Juneteenth creates a space where life can be affirmed, where people of conscience can gather and celebrate Black history and achievement. It is a symbol for what is possible when we work together and also a reminder that we are still working for justice, peace and an inclusive world.

References

Allen, Renee. Quilt artwork entitled Juneteenth.

BlackPast. (2008, September 29). (1865) General William T. Sherman’s Special Field Order No. 15 •. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/special-field-orders-no-15/

Clemmons, I. (1993). And Still the Church Triumphs: Although Challenged, the Nation’s Last Best Hope”. St. Paul’s Anniversary Program, Anniversary Program.

Douglass, F. (1852). Oration. Lee Mann and Company.

Freedom At Antietam (U.S. National Park Service). (n.d.). Retrieved June 11, 2021, from https://www.nps.gov/articles/freedom-at-antietam.htm

GALVESTON.COM: Historical Marker: Juneteenth. (n.d.). Galveston, TX. Retrieved June 11, 2021, from https://www.galveston.com/whattodo/tours/self-guided-tours/historical-markers/juneteenth/

Gramlich, J. (2020, May 6). Black imprisonment rate in the U.S. has fallen by a third since 2006. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/05/06/share-of-black-white-hispanic-americans-in-prison-2018-vs-2006/

Interview with Laura Smalley, Hempstead, Texas, 1941 (part 1 of 5). (n.d.). [Audio]. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved June 11, 2021, from https://www.loc.gov/item/afc1941016_afs05496a/

Jones, M. (2020, January 17). 3/5 Compromise: The Definition Clause that Shaped The Future. https://historycooperative.org/three-fifths-compromise/

Lentz, S. R. (2020, June 18). Juneteenth: Black Americans’ True Independence Day. UT News. https://news.utexas.edu/2020/06/18/juneteenth-black-americans-true-independence-day/

Map of Free and Slave States in 1860 · SHEC: Resources for Teachers. (n.d.). Retrieved June 11, 2021, from https://shec.ashp.cuny.edu/items/show/2008

Marini, R., and Davis, V. (2020, June 18). A powerful celebration of freedom, Juneteenth has spread beyond Texas to the rest of the country. https://www.expressnews.com/news/local/article/A-celebration-of-freedom-Juneteenth-has-spread-15350019.php

Melba Newsome and 2021. (2021, April 6). What is Juneteenth? Taste of Home. https://www.tasteofhome.com/article/what-is-juneteenth/

National Park Service. (n.d.). The Dred Scott Case—Gateway Arch National Park (U.S. National Park Service). Retrieved June 11, 2021, from https://www.nps.gov/jeff/planyourvisit/dredscott.htm

Presidential Proclamation (September 22, 1862) | Lincoln’s Writings. (n.d.). Retrieved June 11, 2021, from https://housedivided.dickinson.edu/sites/lincoln/presidential-proclamation-september-22-1862/

Shaffer, D., and Regosin, E. (2005, Winter). Voices of Emancipation. National Archives. https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2005/winter/voices.html

The Compensated Emancipation Act of 1862. (2018, April 16). We’re History. http://werehistory.org/the-compensated-emancipation-act-of-1862/

The Emancipation Proclamation. (2015, October 6). National Archives. https://www.archives.gov/exhibits/featured-documents/emancipation-proclamation

The First Black Watch Night Service in America. (n.d.). African American Registry. Retrieved June 11, 2021, from https://aaregistry.org/story/the-first-black-watch-night-service-occurs-in-america/

Timeline | Abraham Lincoln and Emancipation | Articles and Essays | Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress | Digital Collections | Library of Congress. (n.d.). [Web page]. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved June 11, 2021, from https://www.loc.gov/collections/abraham-lincoln-papers/articles-and-essays/abraham-lincoln-and-emancipation/timeline/

Timeline of Emancipation. (n.d.). UM Clements Library. Retrieved June 11, 2021, from https://clements.umich.edu/exhibit/proclaiming-emancipation/timeline-of-emancipation/

Trump’s Juneteenth rally in Tulsa to inflame racial tension | Cornell Chronicle. (2020, June 12). https://news.cornell.edu/media-relations/tip-sheets/trumps-juneteenth-rally-tulsa-inflame-racial-tension

Tulsa Race Riot of 1921 | Tulsa Library. (n.d.). Retrieved June 11, 2021, from https://www.tulsalibrary.org/tulsa-race-riot-1921