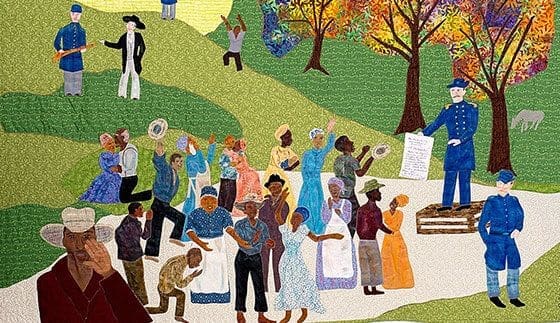

Juneteenth artwork quilt by Renee Allen. Courtesy of Art History Kids

Juneteenth and the Soul of America, Part 1

This two-part blog post is adapted with permission from Juneteenth and the Soul of America, a presentation given for Interfaith Communities United for Justice and Peace (ICUJP) in June 2020.

“I say it with a sad sense of the disparity between us. I am not included within the pale of this glorious anniversary! Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. You may rejoice, I must mourn. To drag a man in fetters into the grand illuminated temple of liberty, and call upon him to join you in joyous anthems, were inhuman mockery and sacrilegious irony.

“Fellow-citizens; above your national, tumultuous joy, I hear the mournful wail of millions! whose chains, heavy and grievous yesterday, are, to-day, rendered more intolerable by the jubilee shouts that reach them.” (Douglass, 1852)

Frederick Douglass, a formerly enslaved person, delivered these words on July 5, 1852, at an Independence Day celebration. They asked, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” This transports us to the crux of our observance of Juneteenth. It speaks to the divided nation, where brothers and sisters in God’s family are set one against another and the deplorable in our worst imaginings becomes real. Juneteenth challenges, in clearly prophetic terms, the premises of our national independence day. It points toward its own hopes and aspirations: the construction of an alternate vision and reality.

Juneteenth has been widely recognized by African Americans and the nation as a whole as a celebration of Black American emancipation from slavery in 1865. Initially celebrated in Texas as Independence Day for African Americans, it tacitly challenged the legitimacy of the 4th of July Independence Day, which Douglass roundly critiqued in his celebrated speech. But since then, Juneteenth has become a national cry for freedom and equality in America – a cry that bursts from the bosoms of African Americans who have been and continue to be treated as less than.

Then and Now

While Juneteenth is seen in a historic light, conditions and problems that existed post–Civil War, when the observance was initially sacralized, continue undeterred in America. These issues center on the dehumanization of Black life, and more pointedly on the deterioration of the American dream and flag under which an entire nation huddles. Moreover, this pernicious evil affects not only African Americans but every other constituency that has worn the label of “other.” This corrosive maleficence affects and inflicts harm on men and women of color, the immigrant, and those maligned due to sexual orientation and health status.

America has witnessed these conditions of dehumanization throughout its history. From the brief honeymoon and experiment of Reconstruction, to the post–Civil War pogroms, Jim Crow era and codified racial segregation, public policy and practices have defined the contours of life, suffering and death for African Americans. In the meantime, the fascination and obsession with Black male as a trope and justification for horrendous evils continues unabated, as evidenced in every segment and sector of American life.

Current events reveal this malaise afflicting the very soul of America. The recent killings of young Black men and women, from Los Angeles, CA and Ferguson, MO to Sanford, FL, Brunswick, GA, Minneapolis, New York and points in between, tell more about us and the State of the Nation than any other sociographic metric or barometer. These killings follow a longstanding tradition of lynchings, disappearances, beatings and physical, cultural and emotional castrations that are synonymous with America.

These acts of police and mob violence on our nation’s streets are compounded by the conspiratorial convergence of corporate greed and a government destined to do its bidding, while playing to the base, reflexive instincts of the larger White population.

Witness, Protest and Hope

To many celebrants, Juneteenth is a time of conviviality, family and community gathering, picnics, barbecues, outdoor performances and festivities, featuring red food and drink. But what does all this have to do with Juneteenth? What does Juneteenth mean to us as Americans? How are we informed and challenged by this celebration?

This writing seeks to offer the Juneteenth celebration as an occasion for witness, protest and hope. It also seeks to galvanize communities of faith and people of conscience with additional insight as a clarion call for change and possibility for America and the world to be just, equitable and participatory.

In the first section, I will provide an overview of the emancipation proclamations, the history of Juneteenth and how it became a nationally observed celebration. The second part will look at the prevailing conditions and challenges that have been constant throughout the country’s history from slavery to the present, as related to Black life and death. The third section studies Juneteenth’s function as an ethical construct. What does Juneteenth have to tell us about our fight for justice, freedom and equality?

Emancipation Proclamations

Contrary to popular knowledge, there was not just one proclamation of emancipation. A number of states had already abolished slavery prior to the Civil War. Pennsylvania was the first state to abolish slavery in 1780. Massachusetts followed in 1783 and New York in 1827. (“Timeline of Emancipation,” n.d.) States were in fact defined on the basis of whether they allowed slavery of not. Thus some states were known as slave states and others as non-slave.

Slavery was practiced primarily in Southern states such as Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, Georgia, Texas, and Arkansas. In the strategy to win the Civil War, Lincoln abolished slavery as a tactic to disrupt the economies of the Southern States and cause crippling disruption in their way of life. (Map of Free and Slave States in 1860 · SHEC: Resources for Teachers, n.d.)

Lincoln also offered formerly enslaved the ability to join the Union army, another threat to Southern states that fed into their worst fears of a deadly insurrection of Blacks. So, heavily tied to his Civil War campaigns, he issued the Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, 1862. The announcement, on the heels of a military success in Antietam, declared all slaves free in the rebel states as of January 1, 1863. (Freedom At Antietam (U.S. National Park Service), n.d.)

Freedom was in the air in Washington, DC, but not for moral or ethical reasons. On April 16, 1862, Lincoln and Congress ended slavery in DC, through the DC Compensated Emancipation Act. It reimbursed those who had legally owned slaves and offered the newly freed women and men money to emigrate. (“The Compensated Emancipation Act of 1862,” 2018)

“Freedom” Inches Closer

In July 1862, Lincoln tested out the Emancipation Proclamation with the Cabinet. Two months later, in September, he issued the Proclamation that freed those enslaved in Confederate states. (Timeline | Abraham Lincoln and Emancipation | Articles and Essays | Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress | Digital Collections | Library of Congress, n.d.)

The first section reads:

To all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free; and the Executive Government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons, and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom. (Presidential Proclamation (September 22, 1862) | Lincoln’s Writings, n.d.)

The proclamation was not across the board and universal. It only applied to states in rebellion and not the enslaved people in border states like Missouri, Kentucky, Delaware and Maryland, which had not joined the Confederacy. Union soldiers read the proclamation as they traveled on plantations and cities in Southern states, triggering large numbers of Blacks running to them for protection and transport. Still, where the newly freed were to go was an entirely different matter.

Read an interview with Mrs. Laura Smalley, a formerly enslaved woman, on her experience

Slavery Abolished at Last

On December 31, 1862, African Americans instituted a “watch night” service as they waited for the Emancipation to go into effect. Watch Night is now a common event in African American churches, where celebrants hold services before midnight to pray in the New Year. (The First Black Watch Night Service in America, n.d.)

The Civil War ended on April 9, 1865. As Texas was the most remote of the slave states, with a low presence of Union troops, enforcement of the Emancipation Proclamation had been slow and inconsistent. Thus, on June 19, 1865, two months and 10 days after the war – and two and a half years after the Proclamation’s signing – Union soldiers went to Galveston, TX and read a general order. Not the Emancipation Proclamation, but a general order based on it that read:

GENERAL ORDERS, No. 3. — The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, “all slaves are free.” This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor.

The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes, and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts, and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.

By command of Maj.-Gen. GRANGER.

(The Emancipation Proclamation, 2015)

Later that year, December 6, 1865, the 13th Amendment was passed, formally abolishing slavery by amending the Constitution.

The First Emancipation Day

On June 19, 1866, the first celebration commemorating this Emancipation took place in Galveston. In fact, it was called Emancipation Day and later became Juneteenth. (Galveston.Com, n.d.) These celebrations grew in number of participants and formality to include a prayer service, speakers with inspirational messages, reading of the Emancipation Proclamation, stories from former slaves, food, barbecue, red soda water, games, rodeos and dances. (Melba Newsome, 2021)

What started out as a Texas celebration became more widespread. Initially, it spread regionally to Louisiana, Arkansas and Oklahoma. Then Juneteenth took on a national character as it gained popularity and African American families migrated to the Northeast, Midwest and West. This migratory pattern took place at various intervals following the Civil War and other times, particularly following World War II. (Marini and Davis, 2020)

Some states still observed their own emancipation or independence days; however, Juneteenth became the national holiday of consensus. In fact, 48 states now recognize Juneteenth as a holiday. (Lentz, 2020)

Many people wonder what happened between January 1, 1863 and June 19, 1865. What took so long? With the Civil War still on, the country was still in a state of conflict. Even in areas where Union troops were in control, enforcing proclamations and rules from Washington was difficult, at best. Also, enslavers intensified efforts to hide their enslaved in territories where the Union troops were less prevalent.

In addition, the Proclamation by itself did not make slaves free. Practical questions arose. Where would one go? Or who would tell Master his negroes are free? What challenges and roadblocks would one encounter in leaving the plantation and finding a road to freedom? The release of Black slaves frequently came at the barrel of the Union guns.